In Northern Renaissance Art the Enclosed Garden Is a Symbol of

Hortus conclusus is a Latin term, meaning literally "enclosed garden". At their root, both of the words in hortus conclusus refer linguistically to enclosure.[i] It describes a genre of garden that was enclosed as a practical concern, a major theme in the history of gardening.[ii]

Having roots in the Song of Songs in the Hebrew scriptures, the term Hortus Conclusus has chiefly been applied as an emblematic attribute and a title of the Virgin Mary in Medieval and Renaissance poetry[3] and art, first appearing in paintings and manuscript illuminations near 1330[4] [5]

The Virgin Mary as hortus conclusus [edit]

The term hortus conclusus is derived from the Vulgate Bible's Canticle of Canticles (also chosen the Vocal of Songs or Vocal of Solomon) 4:12, in Latin: "Hortus conclusus soror mea, sponsa, hortus conclusus, fons signatus" ("A garden enclosed is my sister, my spouse; a garden enclosed, a fountain sealed up.")[6] This provided the shared linguistic culture of Christendom, expressed in homilies expounding the Song of Songs as apologue where the image of Rex Solomon'southward nuptial vocal to his helpmate was reinterpreted equally the honey and union between Christ and the Church building, the mystical marriage with the Church equally the Bride of Christ.

The poesy "Thou art all fair, my dear; there is no spot in thee" (4.7) from the Song was also regarded as a scriptural confirmation of the developing and withal controversial doctrine of Mary'south Immaculate Conception – being born without Original Sin ("macula" is Latin for spot).

Christian tradition states that Jesus Christ was conceived to Mary miraculously and without disrupting her virginity past the Holy Spirit, the tertiary person of the Holy Trinity. Equally such, Mary in late medieval and Renaissance art, illustrating the long-held doctrine of the perpetual virginity of Mary, as well as the Immaculate Conception, was shown in or most a walled garden or yard. This was a representation of her "closed off" womb, which was to remain untouched, and also of her beingness protected, as by a wall, from sin. In the Grimani Breviary, scrolling labels identify the emblematic objects betokening the Immaculate Formulation: the enclosed garden (hortus conclusus), the tall cedar (cedrus exalta), the well of living waters (puteus aquarum viventium), the olive tree (oliva speciosa), the fountain in the garden (fons hortorum), the rosebush (plantatio rosae).[7] Not all actual medieval horti conclusi even strove to include all these details, the olive tree in particular being insufficiently hardy for northern European gardens.

The enclosed garden is recognizable in Fra Angelico'southward Annunciation (illustration at above left), dating from 1430-32.

2 pilgrimage sites are dedicated to Mary of the Enclosed Garden in the Dutch-Flemish cultural area. One is the statue at the hermitage-chapel in Warfhuizen: "Our Lady of the Enclosed Garden". The second, Onze Lieve Vrouw van Tuine (literally "Our Lady of the Garden"), is venerated at the cathedral of Ypres.

Actual gardens [edit]

All gardens are past definition enclosed or divisional spaces, only the enclosure may be somewhat open up and consist only of columns, depression hedges or fences. An actual walled garden, literally surrounded by a wall, is a subset of gardens. The significant of hortus conclusus suggests a more private style of garden.

Medieval-way garden from Coucy, France

In the history of gardens the High Medieval hortus conclusus typically had a well or fountain at the center, bearing its usual symbolic freight (see "Fountain of Life") in addition to its practical uses. The convention of iv paths that divided the foursquare enclosure into quadrants was so strong that the pattern was employed even where the paths led nowhere. All medieval gardens were enclosed, protecting the private precinct from public intrusion, whether by folk or past stray animals. The enclosure might be equally simple equally woven wattle fencing or of stout or decorative masonry; or it might be enclosed past trelliswork tunneled pathways in a secular garden or by an arcaded cloister, for communication or meditative pacing.

The origin of the cloister is in the Roman colonnaded peristyle, as garden histories note. The ruined and overgrown Roman villas that were so often remade as the site of Benedictine monasteries had lost their planted garden features with the first decades of abandonment: "gardening, more than architecture, more than painting, more than music, and far more literature, is an imperceptible art; its masterpieces disappear, leaving little trace."[8] Georgina Masson observed: "When, in 1070, the abbey of Cassino was rebuilt,[9] the garden was described as 'a paradise in the Roman fashion'." But it may take been merely "the aureola of the great classical tradition" solitary that had survived.[ten] The ninth-century idealised plan of Saint Gall (illustration) shows an arcaded curtilage with a cardinal well and cantankerous-paths from the centers of each range of arcading. But when a consciously patterned garden was revived for the medieval curtilage, the patterning came through Norman Sicily and its hybrid culture that adapted many Islamic elements, in this example the enclosed Due north African courtyard gardens, ultimately based on the Farsi garden tradition.

The practical enclosed garden was laid out in the treatise by Pietro Crescenzi of Bologna, Liber ruralium commodorum, a work that was often copied, equally the many surviving manuscripts of its text attest, and oftentimes printed in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Late medieval paintings and illuminations in manuscripts such every bit for The Romance of the Rose – where the garden in the text is largely allegorical – often show a turfed depository financial institution for a seat equally a feature of the hortus conclusus. Only in the fifteenth century, at showtime in Italy, did some European gardens begin to look outward.

Sitting, walking and playing music were the activities most often portrayed in the numerous fifteenth-century paintings and illuminated manuscripts, where strenuous activities were inappropriate. In Rome, a late fifteenth-century cloister at San Giovanni dei Genovesi was constructed for the use of the Genoese natio, an Ospitium Genoensium, as a plaque however proclaims, which provided shelter in cubicles off its vaulted encircling arcades, and a meeting identify and shelter reuniting those from the distant abode city.[11]

Virgin and Child with saints and donor family, Cologne, c. 1430

Somewhat earlier, Pietro Barbo, who became Pope Paul II in 1464, began the construction of a hortus conclusus, the Palazzetto del Giardino di San Marco, fastened to the Venetian Cardinals' Roman seat, the Palazzo Venezia.[12] It served as Paul's individual garden during his papacy; inscriptions stress its secular functions as sublimes moenibus hortos...ut relevare animum, durasque repellere curas, a garden of sublime delights, a retreat from cares, and praise it in classicising terms as the habitation of the dryads, suggesting that there was a central grove of trees, and mentioning its snowy-white stuccoed porticoes. An eighteenth-century engraving shows a tree-covered primal mount, which has been recreated in the modern replanting, with box-bordered cross and saltire gravelled paths.[13]

The Farnese Gardens (Orti Farnesiani sul Palatino – or "Gardens of Farnese upon the Palatine") were created by Vignola in 1550 on Rome's northern Palatine Loma, for Key Alessandro Farnese (1520–89). These become the first private botanical gardens in Europe (the first botanical gardens of whatever kind in Europe being started by Italian universities in the mid-16th century, only a brusk fourth dimension before). Alessandro chosen his summer dwelling at the site Horti Farnesiani, probably in reference to the hortus conclusus. These gardens were also designed in the Roman peristylium manner with a central fountain.[xiv]

Over again in the age of the automobile, the enclosed garden that had never disappeared in Islamic society became an emblem of serenity and privacy in the Western earth.

In fine art [edit]

Hunt of the Unicorn Proclamation (ca. 1500) from a Netherlandish Book of Hours. In this case Gideon's fleece is worked in besides, and the altar at the rear has Aaron'south rod that miraculously flowered in the heart. Both are types for the Announcement.[fifteen]

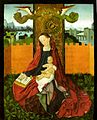

The hortus conclusus was one of a number of depictions of the Virgin in the late Middle Ages developed to be more informal and intimate than the traditional hieratic enthroned Virgin adopted from Byzantine icons, or the Coronation of the Virgin. The subject began every bit a specific metaphor for the Annunciation,[xvi] but tended to develop into a relaxed sacra conversatione, with several figures beside the Virgin seated, and less specific associations. Frg and the Netherlands in the 15th century saw the peak popularity of this delineation of the Virgin, usually with Child, and very often a crowd of angels, saints and donors, in the garden; the garden by itself, to represent the Virgin, was much rarer. Often walls or trellises close off the sides and rear, or it may be shown as open, except for raised banks, to a mural beyond. Sometimes, as with a Gerard David'southward The Virgin and Child with Saints and Donor (beneath) the garden is very fully depicted; at other times, as in engravings by Martin Schongauer, only a wattle debate and a few sprigs of grass serve to identify the theme. Italian painters typically also go along plants to a minimum, and do not take grass benches. A sub-diverseness of the theme was the German language "Madonna of the Roses", sometimes attempted in sculptured altarpieces. The image was rare in Orthodox icons, but there are at least some Russian examples.[17]

One type of depiction, not commonly uniform with right perspective, concentrates on showing the whole wall and several garden structures or features that symbolize the mystery of Christ'southward conception, mostly derived from the Song of Songs or other Biblical passages as interpreted by theological writers. These may include one or more than temple or church-like buildings, an Ivory Tower (SS 7.4), an open-air altar with Aaron'south rod flowering, surrounded by the blank rods of the other tribes, a gatehouse "tower of David, hung with shields" (SS seven.4),[18] with the gate closed, the Ark of the Covenant, a well (oftentimes covered), a fountain, and the morning sun above (SS vi.10).[19] This type of depiction ordinarily shows the Annunciation, although sometimes the child Jesus is held by Mary.[twenty]

A rather rare, late 15th century, variant of this depiction was to combine the Proclamation in the hortus conclusus with the Hunt of the Unicorn and Virgin and Unicorn, and so popular in secular fine art. The unicorn already functioned as a symbol of the Incarnation and whether this meaning is intended in many prima facie secular depictions tin can exist a difficult matter of scholarly interpretation. There is no such ambiguity in the scenes where the archangel Gabriel is shown blowing a horn, equally hounds chase the unicorn into the Virgin's arms, and a piddling Christ Child descends on rays of calorie-free from God the Father. The Quango of Trent finally banned this somewhat over-elaborated, if charming, delineation,[21] partly on the grounds of realism, as no one at present believed the unicorn to be a real creature. In the 16th century the subject of the hortus conclusus drifts into the open air Sacra Conversazione and the Madonnas in a mural of Giovanni Bellini, Albrecht Dürer and Raphael, where it is hard to say if an innuendo is intended.

An exhibition of afterwards medieval visual representations of hortus inclusus was mounted at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington DC;[22] the exhibition drew a stardom betwixt "garden representations as thematic reinforcements and those that seemingly treat the garden equally a subject area in itself"; in reviewing it Timothy Husband, warned against uncritical interpretation of the refined detail in manuscript illuminations' "seemingly objective representation". "Late medieval garden imagery, past subjugating direct observation to symbolic or emblematic intention, reflects more than a state of mind than reality,"[23] if a disjunct can exist detected where the objects of the world shimmered with meaning allegorical meaning. Southward Netherlandish illuminations and painting appear to document the "turf benches, fountains, raised beds, 'estrade'[24] trees, potted plants, walkways, enclosing walls, trellises, wattle fences and bowers" familiar to contemporary viewers, but assembled into an illusion of reality.[25]

-

-

-

-

-

Italian miniature, c. 1435

-

Early woodcut, c. 1460, hand-coloured

-

-

Cologne, ca. 1520

-

-

Woodcut dated 1418, but probably 1450s

Modern cultural references [edit]

The concept for the 2011 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion was the hortus conclusus, a contemplative room, a garden inside a garden. Designed by Swiss architect Peter Zumthor and with a garden created by Piet Oudolf, the Pavilion was a place abstracted from the world of dissonance and traffic and the smells of London – an interior infinite within which to sit down, to walk, to observe the flowers.[26]

Run into likewise [edit]

- Artas, Bethlehem, location of the Catholic Convent of the Hortus Conclusus

- Gaston Bachelard

- Locus amoenus

- Topophilia

References [edit]

- ^ Clifford, A History of Garden design, (New York:Praeger) 1963:17.

- ^ Rob Aben and Saskia de Wit, The Enclosed Garden: History and Development of the Hortus Conclusus and its Re-Introduction into the Present-Day Urban Landscape (Rotterdam) 1999. A typological catalogue of design features and a design transmission.

- ^ Stanley Stewart, The Enclosed Garden: The Tradition and Image in Seventeenth-Century Poetry (Madison: Academy of Wisconsin Printing) 1966, discussed late sixteenth and seventeenth-century verse in English; its four starting time chapters trace the hortus conclusus theme in European literatures and the visual arts.

- ^ Michelle P. Dark-brown, "The Globe of the Luttrell Psalter" British Library 2006,

- ^ Brian East. Daley, "The 'Closed Garden'and the 'Sealed Fountain': Vocal of Songs four:12 in the Late Medieval Iconography of Mary", Elizabeth B. Macdougall, editor, Medieval Gardens, Dumbarton Oaks Colloquium ix) 1986, traced the sudden development about 1400 of painted images of the Virgin Mary in a hortus conclusus.

- ^ The whole text Archived 2011-05-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Timothy Husband, reporting the exhibition and its catalogue in The Burlington Magazine, 125, No. 967 (October 1983:643).

- ^ Clifford 1963, eo. loc..

- ^ The site was that of a Roman majestic villa, as was the site of Bridegroom's monastery at Subiaco, occupying Nero's sometime villa.

- ^ Masson, Italian Gardens (New York: Abrams) 1961:46.

- ^ Wolfgang Lotz, "Bramante and the Quattrocento Cloister" Gesta 12.one/2 (1973):111-121) p. 113.

- ^ Information technology was dismantled and re-erected in 1910 to make space for Piazza Venezia.

- ^ Hinc hortos dryadumque domos et amena vireta/ Porticibus circum et niveis lustrata columnisLotz 1973 eo. loc. and figs 10 and 11.

- ^ "The Roman Forum". www.theromanforum.com . Retrieved 2020-08-eighteen .

- ^ Schiller, 54; similar epitome on panel

- ^ Schiller, pp 52-55

- ^ Russian instance, Tretyakov Gallery Moscow.

- ^ "Thy neck is similar the belfry of David congenital for an armoury, whereon there hang a thousand bucklers, all shields of mighty men."

- ^ "Who is she that looketh forth as the morning, fair as the moon, clear as the dominicus, and terrible as an army with banners?"

- ^ Schiller, pp 53-54

- ^ Gertrud Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I,1971 (English trans from High german), Lund Humphries, London, pp. 52-4 & figs 126-9, ISBN 0-85331-270-2, another image

- ^ Exhibition catalogue, Marilyn Stokstad and Jerry Stannard, Gardens of the Heart Ages, Dumbarton Oaks and Spencer Museum of Fine art, Academy of Kansas (University of Kansas) 1983.

- ^ Husband 1983:644.

- ^ An estrade tree was pruned into a series of diminishing horizontal tiers similar a sweetmeat stand up, the French estrade coming from Spanish estrado, denoting the carpeted and raised section of a room (cf OED, s.v. "estrade", "estrado").

- ^ Husband, eo. loc..

- ^ "Serpentine Gallery Pavilion 2011 by Peter Zumthor". Serpentine Galleries . Retrieved 2020-08-18 .

Further reading [edit]

- D'Ancona, Mirella Levi (1977). Garden of the Renaissance: Botanical Symbolism in Italian Painting. Firenze: Casa Editrice Leo S.Olschki. ISBN9788822217899.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Hortus conclusus at Wikimedia Eatables

Media related to Hortus conclusus at Wikimedia Eatables - Hortus conclusus every bit ane of a number of Devotional Images

- The Garden of Eden, a hortus conclusus by the Master of the Upper Rhineland

- Early Delights, first-class piece past Jemima Montagu on the symbolism of the garden

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hortus_conclusus

0 Response to "In Northern Renaissance Art the Enclosed Garden Is a Symbol of"

Post a Comment